Alberto Abate was “born” into art, in a literal sense, as his father was the Catanian sculptor Carmelo Abate. The story of his own development possesses a particular dramatic quality. Perhaps even more clearly than other artists of his generation, he represents both the acceptance of the extreme Modernist tendencies in contemporary Italian art and the instinctive rejection of them. In the mid-1970s he experimented with Conceptual art is Performance, but only to renounce it toward the end of the decade in favor of a return to painting.

The style of painting he chooses is, perhaps, not what was expected, given the conditions prevailing at the time. Instead of reacting with photographic naturalism-a genre in which there were many precedents at the time of his extraordinary conversion-he is interested in the precedents offered by art that, at that time, was regarded with greater interest by scholars rather than by members of the avant-garde. The influence he received through Renaissance masters such as Pietro di Cosimo and Botticelli is, no doubt, present in his early works such as Encounters, Elegy and Scola Centauri (all three from 1980). Encounters, with the headless figure in the foreground, shows traces of the impact given by Surrealism while the other two paintings mentioned above are purely Renaissance in flavor.

La mossa del cavallo, 1985 – Oil on canvas, cm 120×150

Delfica, 1984 – Oil on canvas, cm 120×100

Abate, however, already aware of the stages traversed in pictorial art between the Renaissance and the ‘rise of Surrealism, quickly developed his own for reciprocal style, totally individual, in which major debt goes to the English Pre-Raphaelites and to aspects of French and Belgian Symbolism at the turn of the century, In particular the work of Gustave Moreau and the Salon de la Rose+Cruise. For example, there is a similarity to the work of French painter Armand Point (1860-1932) whose work mixes Moreau’s influence with that of the Pre-Raphaelites.

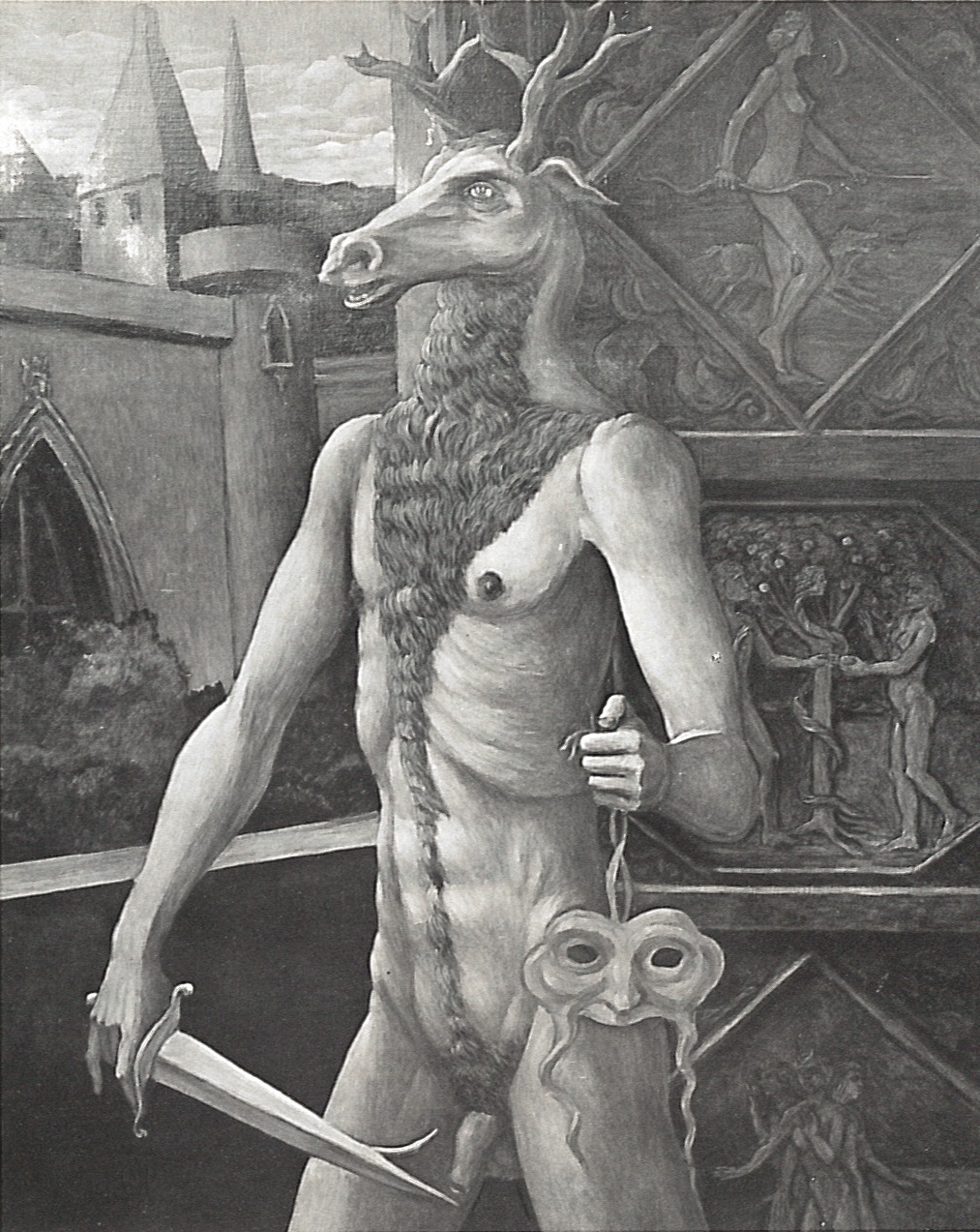

In a sense, from 1980 onward, Abate’s work can be seen as the recovery of a period of an artistic style mysteriously omitted from the continuity of Italian art history. He is fully aware of the controversial nature of the role that is assumed. For example, there are some paintings from the early 1980s (1983 and 1984) more than titled Portrait of the Artist dressed as a Sower of Discord. One of them shows a nude, masked male figure in the bow of stretching a bow. instead of an arrow, the bow is armed with a trident intertwined with a snake.

In the early 1990s, Abate’s compositions become, little by little, confidently more sumptuous. For example, it is worth comparing his Salome of 1991 to the following year’s painting with the same subject. The first painting is not only smaller in size – 90 cm high compared to 180 cm for the second – it is also much more rigorously classical. Salome’s head is like an outline on a Greek coin, and there is little about the composition that suggests the true subject. The tray holding the severed head of St. John the Baptist looks like a rose window adorned with a grotesque mask.

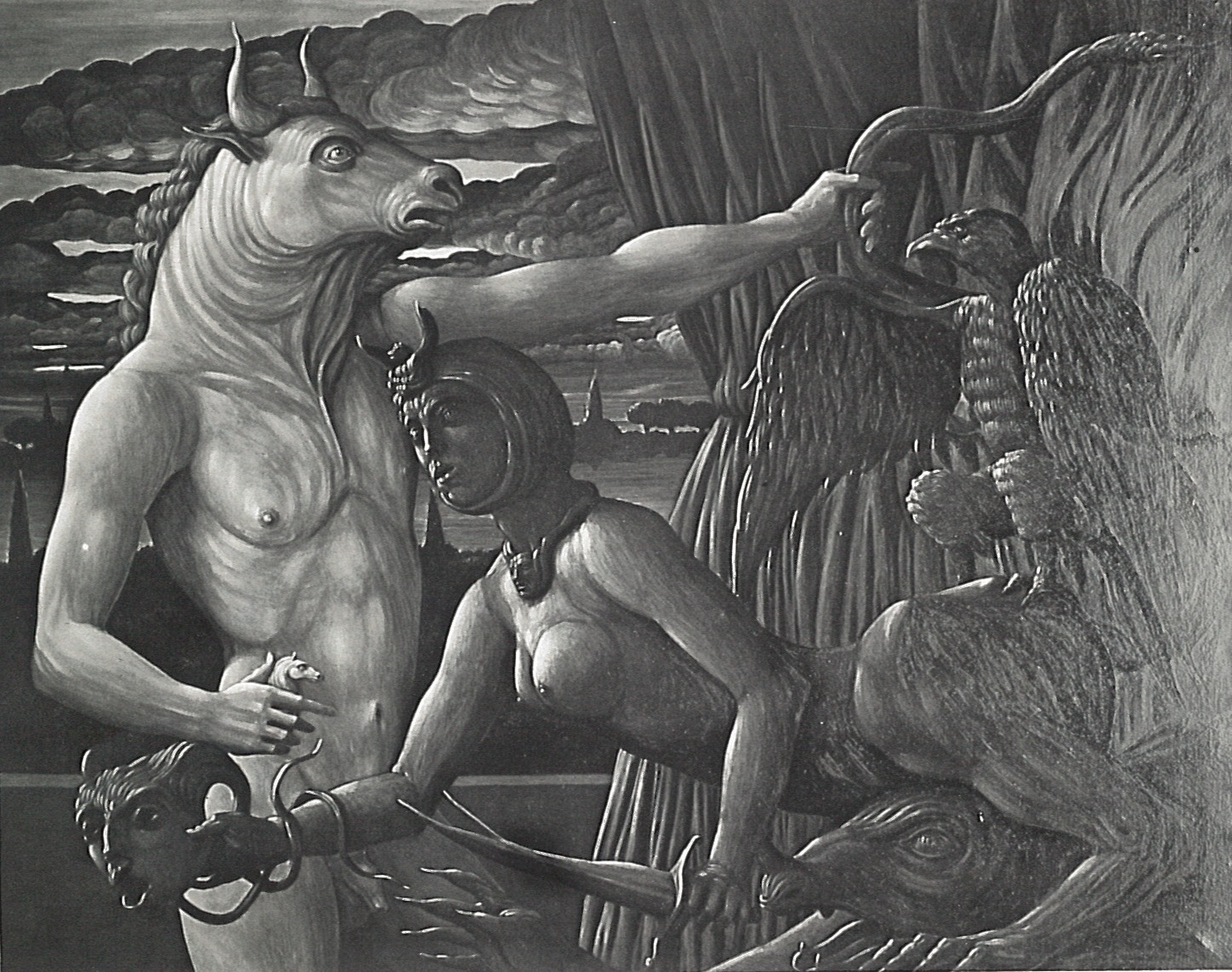

La generazione di Pasifae, 1984 – Oil on canvas, cm 180×200

Eroica 1984 – Oil on canvas, cm 90×70

Mainly, however, Abate’s recent works try to avoid complicated intellectual programs in favor of lavish visual effects.

In essence, what Abate has done is to have uniquely created a personal and recognizable style by taking a large number of examples from the past. Very often, the genre of art he most closely analyzed contained in turn “shooting” elements. I am thinking of his use of artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Gustav Klimt. Nevertheless, it is much more sophisticated than they are. He makes full use of the exceptional range of cultural references that are available to contemporary artists today. None of the predecessors, whom I have mentioned here, could have had so many research sources at their disposal, or even the ability to analyze them in such depth. It is not pejorative to say that Abate is visually greedy-his painting shows how quick his eye is to absorb everything that comes before him.

In general, the paintings of the early 1990s show how Abate turned away from classical influences, heading instead toward the world of the French Symbolists and British Pre-Raphaelites. Some compositions of the period go to mannerist extremes, using the term in a descriptive rather than simply art-historical way.

Anatema, 1982

Oil on canvas, cm 100×80

© 2025 – www.albertoabate.com |All Right Reserved | Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy | Web Design by ADM